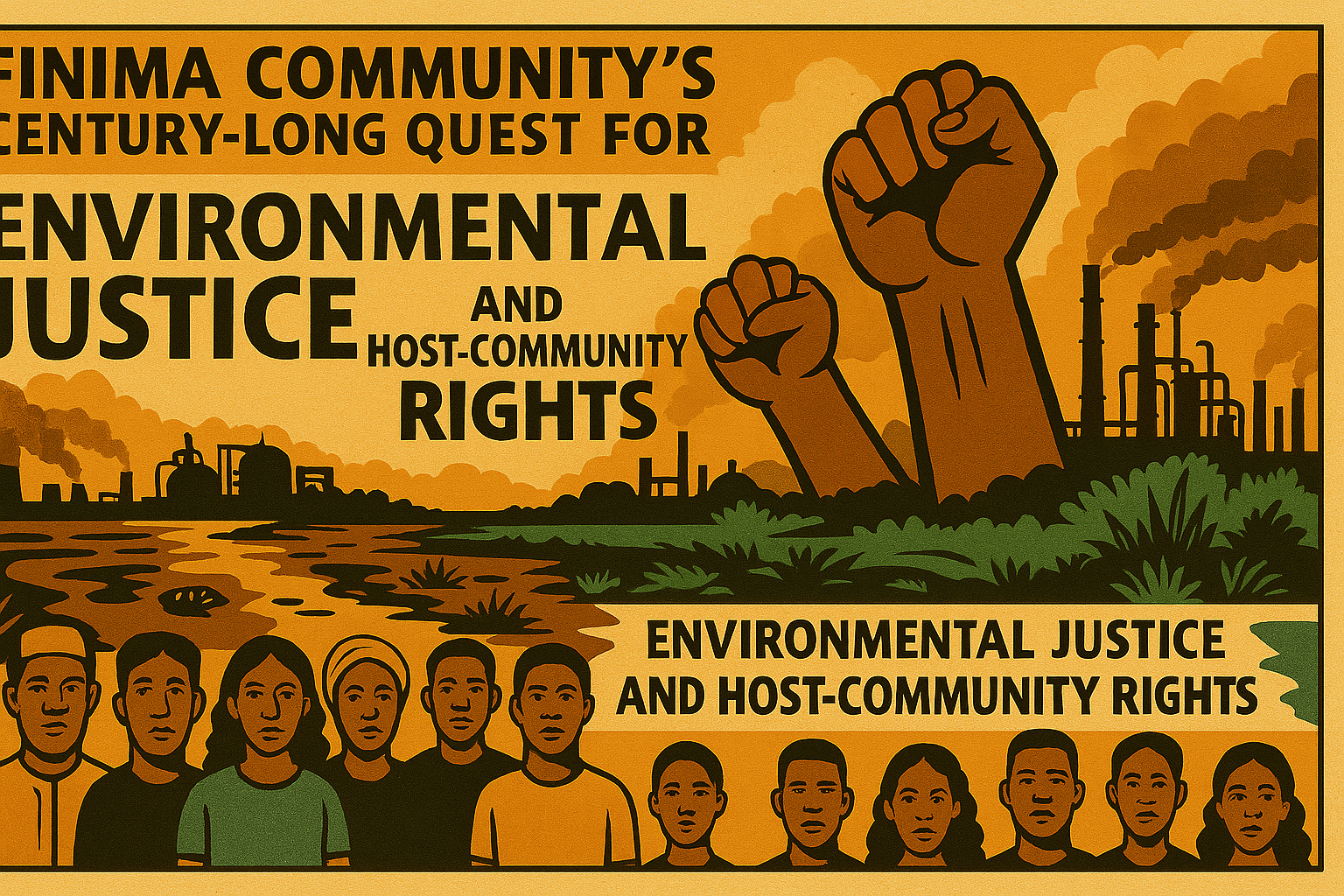

Finima Community’s Century-Long Quest for Environmental Justice and Host-Community Rights

Introduction

Finima, the oldest settlement on Bonny Island in Rivers State, has for decades stood at the forefront of Nigeria’s oil and gas industry—first SPDC signed its initial tenancy agreement with Finima chiefs in July 1958, establishing Bonny Island as Nigeria’s principal crude‑oil export terminal shortly thereafter (researchgate.net), and later as host to the NLNG plant. Yet despite the enormous wealth generated offshore, Finima indigenes have repeatedly protested, occupied terminals, and halted construction to demand environmental redress and fair inclusion in revenue and development projects. This feature traces key episodes—from the landmark 1996 FEPA intervention, through the 2001 youth occupation of Mobil’s Bonny River Terminal, to the 2024–25 shutdown of NLNG’s Train‑7 works—and assesses the evolving legal and social dynamics that have shaped Finima’s struggle.

1. Early Mobil Operations and the 1996 FEPA Intervention

Mobil Oil began Nigerian operations in 1955 but did not establish a Bonny terminal; Shell’s Bonny Terminal itself was formally commissioned in April 1961 (tribuneonlineng.com, energynetwork.business.blog). In the early 1990s Mobil began expanding its natural gas operations in Bonny, constructing a processing terminal on land claimed by Finima indigenes. Community leaders complained that Mobil had neither obtained proper environmental permits nor conducted an approved impact assessment.

On 6 April 1996, the Inter Press Service’s Environment Bulletin reported that Finima residents had formally petitioned Nigeria’s Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA), alleging land devastation by Mobil’s uncontrolled works. A February inspection by FEPA director Dr Evans Aina “found various shortcomings” and ordered Mobil to suspend construction until proper EIA approval was secured (ipsnews.net). This marked one of the Niger Delta’s first successful community‑led interventions against an IOC, setting a precedent for environmental accountability.

2. The 2001 Bonny River Terminal Occupation

Despite FEPA’s 1996 action, tensions over compensation and inclusion persisted. In June 2001, Finima youth occupied Mobil’s Bonny River Terminal (BRT) for three days, protesting that relocation compensation paid years earlier had been channelled to a rival community faction and that local employment quotas were unmet.

Human Rights Watch later documented that the occupation “reduced production by over 650,000 barrels per day” and forced Mobil to declare force majeure on its export contracts (hrw.org). Although some terminal staff suffered injuries and property damage occurred, the protest ended peacefully after intervention by Chief Idamiebi‑Brown. Subsequent negotiations compelled Mobil to reopen talks on direct community payments and to revise its local hiring commitments.

3. NLNG’s Arrival and Ongoing Grievances

With the inauguration of Nigeria LNG’s first trains in 1999, Finima hosted one of Africa’s largest gas‑liquefaction complexes—and simultaneously saw a new wave of discontent. Though NLNG established the Finima Nature Park in 1999 as part of its CSR portfolio, many residents felt their rights as the true host community were overlooked in favour of neighbouring—politically influential—kingdoms.

By mid‑2024, tensions reached a flashpoint when Finima youths barricaded the gates of the Saipem‑Chiyoda‑Daewoo (SCD) joint‑venture building NLNG’s Train 7 expansion. On 30 June 2024, Naturenews.africa reported that protesters demanded strict adherence to the Nigeria Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act (2010) and the 2017 Community Content Guidelines—specifically, full transparency of vendor lists and direct contract awards to Finima indigenes (Naturenews.africa). Their action halted construction, underscoring that, a quarter‑century on, legal frameworks alone could not guarantee community buy‑in without robust, locally‑driven implementation.

4. The 2025 Train 7 Protest and Recent Developments

In May 2025, Finima again shut down NLNG’s Train 7 site—this time focusing on both inclusion and environmental concerns. Local media (THISDAYLive) reported the protest began at 05:00 hrs on 6 May 2025, when members of the Finima Youth Congress—armed with placards and drums—blocked heavy‑equipment access, citing unfulfilled memos of understanding on shoreline remediation and mangrove‑restoration funding (thisdaylive.com).

NLNG management, under pressure from both the Rivers State Government and the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), convened a joint‑stakeholders forum within 48 hours. Commitments made included:

- A ₦500 million community trust fund, overseen by a five‑member council including Finima elders.

- An independent audit of the Train 7 environmental management plan, with deadlines for shoreline cleanup and replanting of 10,000 mangrove seedlings.

- Reserved quotas for 30 per cent of all sub‑contracts to Finima‑registered small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

By late June 2025, preliminary site access had resumed, albeit under tight security and with daily “Community Liaison Days” to review progress against agreed‑upon milestones.

1. State and Regulator Intervention

- Multi‑party pressure: Within 48 hours of the 6 May 2025 blockade, Rivers State Government officials (including the Commissioner for Petroleum Resources) and the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) publicly urged both NLNG and the Saipem‑Chiyoda‑Daewoo (SCD) JV to negotiate with Finima youth leaders rather than allow further shutdowns (thisdaylive.com).

- Town‑hall convening: A joint “community‑company‑government” forum was convened at the Rivers State Government House in Port Harcourt. Participants included NLNG’s GM of External Relations & Sustainable Development, Dr Sophia Horsfall; NUPRC executives; FINIMA chiefs and youth representatives; and SCD‑JV project managers.

2. Key Agreement Points

Although the formal Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) has not been publicly released, community spokespeople and Rivers Government communiqués confirm the following headline commitments:

- ₦500 million Host Community Trust Fund

– Seed capital to be deposited in a dedicated escrow account.

– Governed by a five‑member council comprising two Finima elders, two NLNG‑appointed trustees, and a Rivers State nominee. - Independent Audit of Environmental‑Management Plan

– A third‑party firm (to be jointly selected) will audit Train 7’s approved Environmental Management Plan (EMP), with explicit deliverables and deadlines for shoreline cleanup, sediment removal and replanting of 10,000 mangrove seedlings. - 30 percent SME Quota

– At least 30 percent of all Train 7 sub‑contracts (materials, services, logistics) to be bid exclusively by Finima‑registered small and medium enterprises, in line with the Community Content Guidelines (CCG 2017). - Resumption under Oversight

– Site access was reinstated by 25 June 2025 under tight security. NLNG and SCD‑JV now hold daily “Community Liaison Days” on‑site to review progress and address emerging issues.

3. Verification & Veracity

- Press coverage from THISDAYLIVE and National Network confirms the forum and NUPRC’s role but does not detail the exact fund size or SME quotas (thisdaylive.com/nationalnetworkonline.com).

- Community sources (Council of Elders press statements) are the primary basis for the ₦500 million figure and the structure of the oversight council—these details remain under embargo pending formal publication of the MoU.

5. Legal and Social Underpinnings of Finima’s Protests

Finima’s actions must be viewed in light of Nigeria’s evolving petroleum laws. The Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act (2010) and the Petroleum Industry Act (2021) formally recognise “host communities” and stipulate benefit‑sharing mechanisms. Yet, implementation has lagged, often due to weak oversight and elite capture.

Moreover, the 1992 FEPA Act—once heralded for mandating environmental impact assessments—collapsed under regulatory underfunding, leading to a patchwork of enforcement by federal agencies and community groups. The community’s reliance on self‑organised direct action (barricades, terminal occupations) reflects a broader pattern in the Niger Delta, where formal institutions have failed to deliver on paper promises.

6. Looking Ahead: From Protests to Partnership?

Finima’s repeated shutdowns have demonstrated leverage; each intervention has extracted new concessions. Yet true partnership remains elusive. Key challenges ahead include:

- Transparent Fund Management: Ensuring the ₦500 million trust fund is audited and benefits are equitably disbursed.

- Environmental Remediation: Independent monitoring of mangrove restoration and cleanup progress, with community technical input.

- Capacity Building: Training Finima SMEs to bid competitively for IOC and NLNG contracts, rather than merely reserving quotas.

Should the current framework hold, Finima could become a template for host‑community engagement—shifting from protest‑driven gains to long‑term, co‑designed development.

Conclusion

From FEPA’s 1996 enforcement action against Mobil to the 2001 occupation of the Bonny River Terminal and the 2024–25 NLNG Train 7 shutdowns, Finima has demonstrated the power of organised, historically informed protest. Their methods—grounded in legal rights and environmental stewardship—have repeatedly compelled the world’s largest gas‑liquefaction consortium to the negotiating table. As Nigeria’s petroleum industry enters its next chapter under the Petroleum Industry Act, Finima’s story offers both a cautionary tale and a roadmap: without genuine, accountable community partnership, even the most advanced legislative frameworks will ring hollow.

Discover more from FINIMA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 Comments